The secrets to dealing with a passive aggressive team member

Managing a successful team involves getting the best out of different personalities and helping...

This second blog, based on research by Drs Samantha Evans and Catherine Robinson from Kent Business School, University of Kent, presents an update on current UK labour market trends including an analysis of the so-called Great Resignation. Are we seeing data to back up the claims?

Subscribe to our free quarterly Labour Market Trends newsletter to receive each of these blogs directly to your in-box. In addition, you’ll be provided a link to a PDF of the original academic report each blog is based on including more nuanced insights, data and full references.

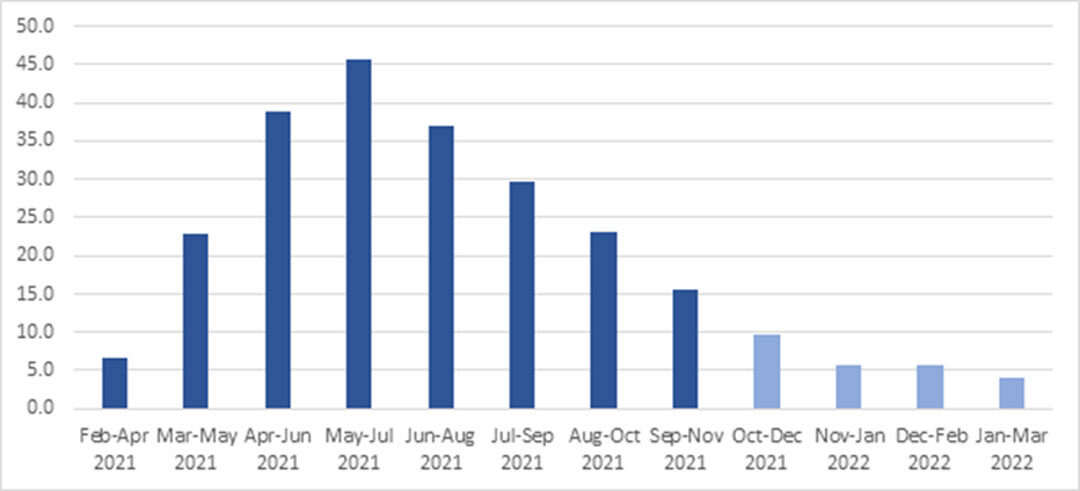

The combination of Brexit and Covid has caused unprecedented shocks to the UK labour market. And although job vacancies remain at a historically high level (and are still climbing), there may be the tiniest glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel. As the below chart shows, growth in vacancies has shown a marked slowing since its apex May – July 2021. The latest data shows just a 4.1% increase.

Percentage change in vacancies (3 month rolling average)

However, there are still significant challenges currently facing recruiters in the UK. The decline in unemployment rate has resulted in one candidate per vacancy. And the candidate shortage, exacerbated by Brexit, is expected to have negative implications for economic growth, especially when combined with a high inflation rate. In addition, there is significant concern that many workers have opted not to return to the labour market post-pandemic in a so-called “Great Resignation.”

In this quarterly insight, we focus on the trends in labour supply and its effect on regions, occupations, and industries. We also look at the “Great Resignation” question: Are resigning workers taking up other jobs elsewhere in the labour market? Or are we seeing a reduction in labour market participation?

Let’s look at the changes across sectors, and employee demographics. For UK data, we turn to the Annual Population Survey, which provides yearly snapshots of labour market participation by region, age band and gender.

One significant change has been that working mothers are 1.5 times more likely to have stopped work than fathers. In addition, women are more likely to be looking for a new role than they were just a year ago. Burnout is cited as the top driving factor, with over half of women wanting to leave their employer in the next two years.

In the graph below, you can also see that men’s participation in the labour market is higher than women’s through all stages of life except at the youngest age band when they enter higher education. However, you can also see that men have declined at a faster rate than women since the start of the pandemic.

One thing to note is that this graph only reports on full-time positions. It’s possible there’s been an increase relative to part-time positions.

UK Labour Market Participation Rates by Gender (2016 – 2021) | Source: Annual Population Survey

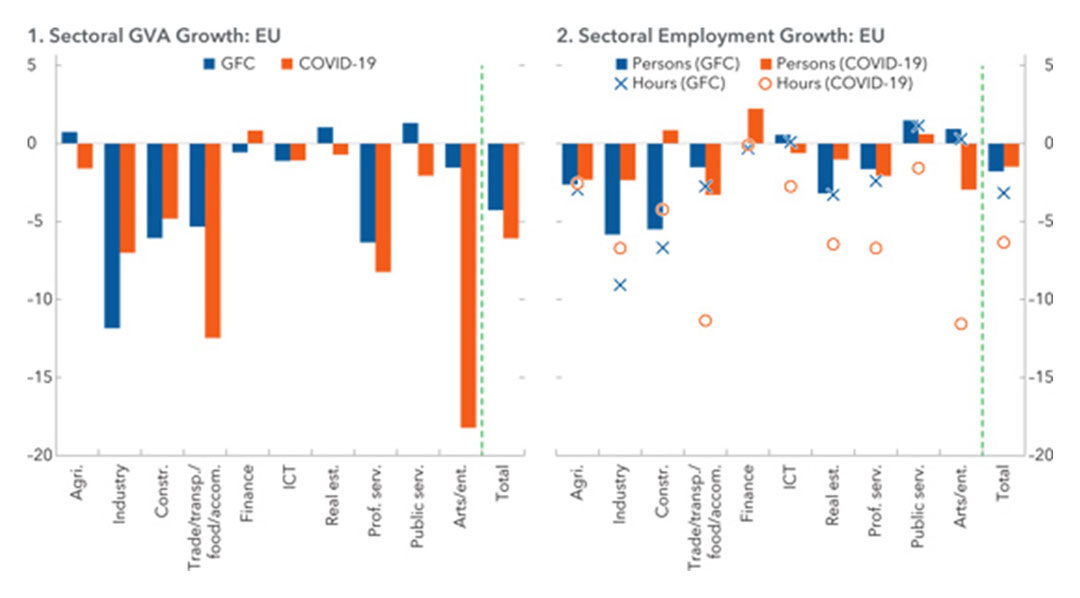

We can see throughout history that economic shocks often result in changes in the labour market. The dot.com crash of the 2000s affected technology workers. The Great Recession/Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in the 2007-09 period had a significant impact on financial sector workers, construction, and manufacturing (industry). The graph below shows the effects of the GFC and the pandemic on sectoral growth.

Sectoral Gross Value Added and Employment Growth, GFC versus COVID-19 Crisis – 2022 | IMF Calculations, Eurostat Data

The Covid-19 pandemic has had wider and further-reaching sector and occupation implications. Hospitality and travel virtually ceased operations overnight, while health and social care saw rapid increases due to pandemic needs. Some of these changes are expected to have long term consequences because they included technological shifts to create new opportunities.

For skills data, we look at a 2021 study on early occupational changes brought about by the pandemic for graduates compared to non-graduates. The findings are based on data from Q1 and Q2 to Q2 and Q3 of 2020. This snapshot shows that graduate vs non-graduate occupational change fluctuated over the quarter. In the beginning of 2020, more graduates changed occupation, while Q2 and Q3 showed more non-graduate occupational change. Overall, graduates show advantages in both scenarios. This group demonstrates more stability in employment due to their roles allowing more remote/online work. In addition, when moving occupation, they benefit from more transferable skills. In contrast, early evidence suggests skills mismatch for non-graduates.

The pandemic has also been shown to increase existing inequalities, with males in higher pre-pandemic unemployment regions in the UK being the slowest to find their way back into the labour market. This could provide an opportunity for recruiters to look in those areas to find their new hires when feasible. See the latest data on unemployment claims by city or town throughout the UK.

In another regional change, a 2021 study shows that urban centres with high international connectivity experienced greater transmission at the start of the pandemic. The adaptation to remote working was accelerated in these settings particularly among knowledge workers. The extent to which this will change the balance between urban and rural workplaces is an interesting question. For example, an OECD study of regions illustrates that London and the Southeast are two of the top 15 areas for capacity for remote working.

The so-called Great Resignation is a term that was coined by an American academic in May 2021 describing a predicted mass exodus of workers in the US leaving their jobs post-pandemic. It has been widely reported in the media worldwide as factoring into candidate shortages. However, there is some debate about its causes – especially when applied to countries other than the United States. Is the UK experiencing the same levels of job quits as the US? And should employers in the UK be concerned?

One argument is that if the UK is experiencing the Great Resignation, it is simply the result of pent-up resignations following the uncertainty of the pandemic, rather than an increased rate of withdrawal from the labour market. For example, analysis of Labour Force Survey data suggests that quit rates in the UK towards the end of 2021 were actually below the average pre-pandemic quit rates for the time of year. While quit rates did rise in the Autumn of 2021, they generally rise in the autumn of any year meaning there is no indication that they have reached dizzying new heights. Another hypothesis is that current labour market trends should instead be termed the “great re-evaluation” as employees rethink their relationship to work, how it fits into their lives and aligns with their values.

There is significantly more evidence for the Great Resignation in the US. In a 2022 report, the US showed clear evidence of an increase in the growth rates of quits amongst older age groups, particularly for the 45-50 age bracket. In addition, the data show that from Q1, 2021 to Q1, 2022 there was a 71% increase in resignations by those who have been in their role for 15-20 years. This is concerning because these leavers are very different from the usual source of labour market churn – who typically are young and less skilled. A more worrying trend for the US is the increased quit rate among knowledge workers. Currently, there is little evidence for this phenomenon in the UK. But it is certainly a trend for employers to look out for in the coming months.

In any event, the candidate shortage is real here too. Many UK employers are struggling to adjust their talent needs and acquisition. Analysis in the US by Gallup suggests that the Great Resignation is less an industry, role, or pay issue, and instead more of a workplace problem. This is actually good news for employers, because it implies that labour turnover rates can be reduced by focusing on internal factors.

Research has found that successful strategies include:

Something to note: One overriding factor is attributed to high labour turnover and poor staff recruitment, and that’s organisational culture. Research has found that a toxic corporate culture is a whopping 10.4 times more powerful than compensation in predicting a company’s attrition rate. So, prioritising organisational culture is an important strategy all organisations can adopt in response to current labour market challenges.

The question remains: to what extent should UK employers be concerned about the Great Resignation? Even if the phenomenon is to be believed, predictions of a recession for many economies may well stem the tide as jobs become scarcer. However, employers need to acknowledge that many of the changes we are seeing in the labour market today are unlikely to be undone. And those companies who rise to the challenge will reap the long-term rewards in the talent market.

We see a number of issues that are likely to become increasingly relevant in the next 6-9 months:

Sign up to the FREE quarterly Labour Market Trends newsletter for downloadable PDFs of the complete academic reports. Get additional research, more nuanced insights and links to source data. Just click the button below, fill in the quick form and you'll receive an immediate email with links to downloadable PDFs of the academic reports from our Kent University partnership. You'll also receive the next two Labour Market Trends newsletters straight to your inbox.

If you're struggling to fill roles, find out how we can help you find the staff you need. Need immediate assistance? Go straight to our National Sales contact page.

Managing a successful team involves getting the best out of different personalities and helping...

Chances are, you’re one of the 364 million people who have a profile on the business networking...